Loading...

32+ YEARS OF RESEARCH WORK ENCOMPASSES

Analytical Styles in Āgamic Literature

The elements of Āgam are profoundly subtle and deep. Like the face of a Gomukhi lion appears calm on the outside but holds immense hidden power, Āgamic scriptures, though seemingly simple, encapsulate profound mysteries. To make these comprehensible even to a general audience, the content has been categorized into various analytical styles, explained below:

ARRANGEMENT OF ALTERNATIVES

1. Bhānga

The Bhānga style is an analytical method where multiple possible combinations and permutations of a concept are presented to explain its comprehensive scope.

Purpose of Bhānga Style:

- To explore every possible variation of a concept

- To help in understanding complex doctrines through structured breakdowns

- Often used in ethical and behavioral classifications in Jain scripture

Example:

The Six-Fold Vows of a Śrāvaka (Lay Follower)

One such instance is the Pachchakhaṇ (vow of renunciation) relating to refraining from sinful acts — both directly and indirectly, and through three mediums: mind, speech, and body.

These form six permutations as shown below:

| Sr. No. | Medium | Action Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mind | Own action | Does not commit sin mentally |

| 2 | Mind | Instigating others | Does not cause others to sin mentally |

| 3 | Speech | Own action | Does not commit sin verbally |

| 4 | Speech | Instigating others | Does not cause others to sin verbally |

| 5 | Body | Own action | Does not commit sin physically |

| 6 | Body | Instigating others | Does not cause others to sin physically |

This structure is an excellent example of Bhānga-style presentation, enabling a clear grasp of the multi-dimensional scope of a single vow.

CONTEXTUALLY ALTERED MEANINGS

2. Sandarbha-the-Viśeṣārtha

Certain words in Jain scriptures — and language in general — may carry different meanings depending on their surrounding context. This method is known as Sandarbha-the-Viśeṣārtha, or "Reference-to-Context Interpretation".

Key Idea:

- The literal meaning of a word may not always reflect its intended meaning.

- The context, including surrounding words and circumstances, determines the accurate interpretation.

Examples of Contextual Variations:

🔹 Lok

The term Lok may imply:

- The realm of living beings (Prāṇiloka)

- The human world (Mānuṣya-loka)

- A gathering or society (Loka-samūha)

Each usage depends on where and how the word appears.

🔹 Hit

- In one scripture, Hit might denote Mokṣa (liberation).

- In another, it forms the compound Hitopāya, interpreted as the trio of Jñāna (Knowledge), Darśana (Faith), and Cāritra (Conduct) — paths that lead to Mokṣa

Modern Language Example:

The acronym IST usually stands for Indian Standard Time.

However, in casual speech:

"He will come according to IST."

...might imply the person is expected to arrive late, referencing a stereotype rather than the literal time zone. Thus, IST here contextually means delay.

Purpose of This Style:

This method reveals how subtle meanings, often not found in dictionaries, can be authentically derived from scriptural or situational context. It's especially important in Jain philosophy, where word precision deeply affects doctrinal clarity.

SYNONYMS – WORDS WITH SIMILAR MEANINGS

3. Paryāyavācī

In this analytical style, different words that convey the same meaning are grouped and presented together. This approach helps in:

- Enhancing vocabulary with scripturally equivalent terms

- Clarifying how different expressions may refer to the same concept

- Demonstrating the richness of language in Jain philosophical texts

Example:

Synonyms for "Sādhu" (Ascetic)

The word Sādhu (a Jain monk or renunciant) is often referred to by several synonymous terms in scriptures:

| Word | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Yati | One who exercises self-restraint |

| Śramaṇa | One who strives spiritually through effort and austerity |

| Saṃyata | One who is controlled and disciplined in thought, word, and deed |

Each term highlights a particular quality or aspect of a Sādhu, yet all refer to the same spiritual identity.

Purpose and Importance:

- Avoids repetition in texts while maintaining depth

- Offers diverse expressions of the same principle

- Enhances the reader's understanding by showing conceptual equivalence

ONE WORD, MULTIPLE MEANINGS

4. Anekārtha

The Anekārtha style focuses on words that possess multiple meanings based on their etymological roots or traditional usage. Such words can convey entirely different ideas in different contexts — and recognizing this is essential for proper scriptural interpretation.

What is Anekārtha?

- A single word carries divergent meanings.

- The meaning varies by context, historical usage, or linguistic derivation.

- This style helps avoid misinterpretation by acknowledging all possible senses of a term.

Example:

The Sanskrit Word "सैंधव" (Saindhava)

| Usage Context | Meaning |

|---|---|

| In dietary context | Salt |

| In animal reference | Horse |

Despite being the same word, "Saindhava" means entirely different things depending on how and where it is used.

Why It Matters:

- Aids in understanding scriptural nuance

- Helps distinguish literal vs. symbolic meanings

- Ensures clarity in philosophical discussions where one term might imply multiple layers of significance

This section compiles such scripturally accepted but lesser-known polysemous words (anekārtha śabdas) that are essential for in-depth Jain study.

CITATION – SCRIPTURAL & PHILOSOPHICAL REFERENCES

5. Uddharaṇa

The Uddharaṇa style is used to validate and enrich explanations by quoting revered individuals, scriptures, or authoritative texts. These references lend credibility and connect present ideas with the timeless wisdom of the Jain tradition.

Purpose of Uddharaṇa:

- To strengthen a point using scriptural or historical validation

- To demonstrate the continuity of truth across time, cultures, and contexts

- To highlight timeless principles that remain relevant even as worldly systems change

Key Insight: The Eternal vs. the Temporary

- The world constantly changes, and history is witness to this.

- Even scientific theories, once thought unshakable, evolve or get discarded over time.

- Beliefs based on such impermanent foundations are like buildings with shaky bases — destined to collapse.

Just as governments and constitutions undergo reforms, philosophies not grounded in eternal truths eventually fade or transform.

Contrast: Unchanging Eternal Principles

- What stands the test of time are eternal truths, which never change.

- Bhagavān Mahāvīra's teachings, spoken over 2500 years ago, reappear unchanged even in texts written 500 years later.

- Ācārya Hemacandra, 900 years ago, and Upādhyāya Yaśovijaya, after the Mughal invasions, both echoed these same principles.

- Even in today's 21st century, the same doctrines continue to be cited and discussed.

This consistent, timeless echo is a testament to omniscient knowledge (Sarvajñatā).

Supreme Authority of Jinavacana

- Due to this permanence, Jināgamas (canonical Jain scriptures) are regarded as the highest authority.

- When a statement is authenticated by Jinavacana (words of the Jina), it is automatically accepted as truth.

- Great scholars like Śrī Haribhadrasūri and Kalikalasarvajña Śrī Hemacandrasūri consistently backed their assertions with Agama-based citations.

What This Section Covers:

- Compilation of various scriptural verses and formulations

- Where they appear, how they are used, and the context of their application

- The themes and meanings they convey across different time periods

CONCISE COMPILATION OR SUMMARY TECHNIQUE

6. Saṅkṣipta Saṅkalana

The Saṅkṣipta Saṅkalana style refers to the art of distilling vast scriptural content into clear, brief, and structured summaries. This style is especially useful for learners, scholars, and practitioners who aim to grasp, retain, and apply complex Jain doctrines quickly and effectively.

Purpose of This Style:

- To make lengthy, intricate topics easily digestible

- To aid in memorization and understanding

- To highlight the core message without losing depth

How It Works:

- Broad scriptural discussions are converted into bullet points or brief explanations.

- Complex metaphysical concepts are condensed without distorting their meaning.

- Logical flow and semantic clarity are maintained throughout.

Benefits of Concise Compilation:

- Greatly reduces cognitive overload

- Allows faster revision of key concepts

- Enhances communication and teaching of Jain philosophy

- Serves as an effective reference tool for debates or studies

BHEDA–PRABHEDA: CLASSIFICATION THROUGH HIERARCHICAL TREES

7. Tree

In Jain scriptures, many topics involve a complex hierarchy of types and subtypes, known as Bheda-Prabheda. These are best understood through the Tree Format — a parent-child structure that visually lays out the relationships between main concepts and their subdivisions.

Why Use the Tree Format?

- Jain texts often present multiple types of a single concept.

- For example, in Jīva-vicāra (the study of living beings), there are 563 distinct classifications of Jīvas.

- Without a clear structure, it's difficult to memorize and comprehend these divisions.

Structure of the Tree Format:

- Parent: The main concept or category

- Child: Subcategories branching out from the parent

- Sub-child: Further divisions from each child node

This format creates a step-by-step hierarchical view, much like a flowchart or family tree, which is:

- Easy to visualize

- Logical in sequence

- Memory-friendly

Visual and Practical Value:

- Presents complex knowledge in a compact visual schema

- Enhances understanding through relational mapping

- Useful for both study and teaching, especially in comparative or categorical analysis

FOUR-PART LOGICAL DIVISION

8. Catuṣbhangī

The Catuṣbhangī method divides a subject into four distinct combinations, formed by pairing two opposing terms from one category with two opposing terms from another. This classical style is used to demonstrate subtle distinctions and combinations in Jain philosophical analysis.

Structure of Catuṣbhangī:

- Two concepts (e.g., Hiṃsā and Ahiṃsā)

- Combined with another set of two concepts (e.g., Dravya and Bhāva)

- Resulting in four possible permutations or logical "breakdowns"

Illustrative Example:

Hiṃsā (Violence) vs. Ahiṃsā (Non-violence) paired with Dravya and Bhāva

| Type No. | Combination | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Dravya Hiṃsā – Bhāva Hiṃsā | External violence has occurred (e.g., beings killed), and internal negligence exists due to ajñāna (ignorance) or upekṣā (carelessness). |

| 2 | Dravya Hiṃsā – Bhāva Ahiṃsā | Physical violence happens outwardly, but the person follows Iryā-samiti (careful conduct) mindfully, so no inner violence is attributed. |

| 3 | Dravya Ahiṃsā – Bhāva Hiṃsā | No physical violence occurs, but due to absence of right awareness or care, inner violence is still considered present. |

| 4 | Dravya Ahiṃsā – Bhāva Ahiṃsā | No external violence happens, and conduct is executed with mindful restraint — representing both physical and emotional non-violence. |

Use and Significance:

- Simplifies the understanding of dual-layered doctrines

- Highlights ethical subtleties in Jain conduct

- Enables scholars to categorize complex behaviors with precision

This section presents such doctrinal elements in four-part logical formats for clear comprehension and comparative insight.

DIVERGENT VIEWS OR INTERPRETATIVE VARIATIONS

9. Matāntara

The Jain scriptures are characterized by Anekāntavāda (multiplicity of viewpoints) and are spoken by the Sarvajña (omniscient). While each subject has a definitive and singular form depending on the perspective adopted, several reasons over time have led to varied interpretations:

Reasons for Divergence:

- Historical challenges and adversities faced by the Jain tradition

- Increasing forgetfulness among people

- Differences in regional and sectarian traditions

- Gaps in scriptural study and practice

Due to such circumstances, when a subject—especially one beyond direct sensory perception or beyond temporal-spatial relevance—presents itself with multiple scriptural statements that seem to differ, it becomes difficult for an ordinary person to arrive at a precise conclusion.

Scriptural Approach to Divergence:

- Early Ācāryas themselves acknowledged these variations.

- They employed logical inference (anumāna) to navigate such complexities.

- All divergent views (matāntara) were recorded with sincerity and integrity.

- Often, they would clarify openly:

"Tattvaṃ tu Kevaligamyaṃ" — "Only the Kevalajñānī (Omniscient One) can fully comprehend the absolute truth of this matter."

Rather than outright rejecting any position, the decision was respectfully deferred to the omniscient authorities. Such reconciliations have been compiled under this style of Matāntara.

Divergence by Naya (Viewpoints):

Sometimes, apparent contradictions arise not from opposition, but from differing naya (philosophical standpoints):

- For instance, the spiritual state of Samyaktva (right belief) is considered to arise at the 4th Guṇasthāna from the Vyavahāra Naya (conventional standpoint).

- However, the same is recognized at the 7th Guṇasthāna under the Niścaya Naya (absolute standpoint).

- Both views are valid within their respective frameworks and are not contradictory.

STEP-BY-STEP HIERARCHICAL DESCRIPTION

10. Kram

In Jain Āgamic tradition, especially in matters of Ācāra (conduct), the scriptures outline a principle-based step-wise approach that follows the logic of Utsarga (primary rule) and Apavāda (exception).

Sequential Rule Structure:

- Utsarga: The default or ideal action, to be followed without reason for deviation. This is considered the purest mode of conduct.

- Apavāda: If following the Utsarga is not possible due to circumstances, the scriptures prescribe an alternative that involves lesser transgression.

- Further gradations are provided if even the first alternative is unachievable, progressively listing options with slightly higher allowances of fault.

This structured gradation helps ensure that ethical conduct is maintained even in difficult or constrained situations.

Illustrative Example:

(Bhikṣā and Panchakahāṇi):

- A Sādhu ideally should obtain alms (Bhikṣā) from 42 faultless sources—this is the Utsarga.

- If these are unavailable, a second-best option with minor faults is permitted.

- If that too is unattainable, the next permissible alternative with slightly more faults is allowed.

- This progressive set of fallback options is known as Pañcakahāṇi in Jain terminology.

Practical Case: Crossing a River

When a Sādhu needs to cross a river, and ideal methods are not feasible, the scriptures specify an order of permissible actions, beginning with the least fault-laden method.

Such graded alternatives are provided across various practical scenarios and are documented under this section to demonstrate how conduct can adapt responsibly without breaching core ethical principles.

UNDERSTANDING THROUGH QUANTITATIVE COMPARISON

11. Alpabahutva

The Jain scriptures frequently employ the analytical method of Alpabahutva, where elements are explained through comparative enumeration — moving from lesser to greater quantities. This style aids in building conceptual clarity and memory through relative comparison.

Principle of Alpabahutva:

When multiple categories or subtypes exist, they are often presented in a progressive order:

- Begin with the item of smallest quantity

- Proceed to items of progressively greater quantity

- Emphasize relative magnitude across categories

Illustrative Example:

Classification of Jīvas

In works like Pañcasaṅgraha, the classification of living beings (Jīvas) across the four Gatis (destinies) results in 94 types. Among these:

- The least numerous are the Garbhaja Parayāpta Manuṣyas (womb-born, fully developed humans).

- Next are the Parayāpta Bādar Teukāyas — beings that are innumerably more than the former.

- Beyond them are the Anuttaravāsī Devas (highest celestial beings), who are countless times more numerous than the previous group.

This hierarchy of quantity helps one grasp complexity through comparison, which the scriptures apply to thousands of concepts.

Purpose & Value:

Such gradations are not merely statistical — they help:

- Comprehend cosmological vastness

- Visualize spiritual hierarchies

- Understand relative spiritual merit or conditions

This section compiles such comparative patterns where "lesser to greater" logic is applied across scriptural topics.

USAGE OF A WORD IN MULTIPLE CONTEXTS

12. Nikshepa

The Jain analytical style of Nikshepa (multi-level interpretation) enables a word to be understood through several dimensions, helping distinguish between surface usage and deeper meaning.

Four Core Nikshepas:

Every word can be interpreted through at least four types of perspectives:

- Nāma Nikshepa — Based on name only

- Sthāpanā Nikshepa — Based on representation or installation

- Dravya Nikshepa — Based on substance or form

- Bhāva Nikshepa — Based on inner disposition or spiritual state

These categories allow for sub-classification into even more specific meanings depending on temporal knowledge and functional state.

Illustrative Example:

The Word "Maṅgala"

Let us explore how the word Maṅgala can be broken down according to the Nikshepa system.

📌 Maṅgala Word Interpretations:

| Type | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Nāma Maṅgala | Someone named Maṅgala |

| Sthāpanā Maṅgala | A photo or image representing Maṅgala |

| Āgama Dravya Maṅgala | One who knows the meaning but isn't currently applying it |

| Anāgama Jñāśarīra Dravya Maṅgala | The dead body of someone who once knew the meaning |

| Anāgama Bhavyaśarīra Dravya Maṅgala | One who doesn't currently know but will in future |

| Anāgama Tadvyatirikta Dravya Maṅgala | Widely known symbols like Aṣṭamaṅgala |

| Āgama Bhāva Maṅgala | One who knows and actively applies the meaning |

| Anāgama Bhāva Maṅgala | Possessors of five Jñānas; includes Tīrthaṅkaras |

Why Nikshepa Matters:

- Helps clarify which exact meaning is being used in scriptural context.

- Ensures precision when interpreting philosophical or doctrinal terms.

- This layered and methodical analysis is a unique contribution of Jain epistemology — not found in other religious traditions.

CHART–TABLE FORMAT

13. Koṭhā–Koṣṭaka

In Jain scriptural analysis, certain topics are often interconnected with other concepts, making it helpful to present them using tables or charts. This structured visual approach aids in better memory retention and easier comprehension.

What is Koṭhā–Koṣṭaka:

- Data is organized in row and column headers representing two interrelated dimensions.

- The intersections (cells) are filled with relevant correlating information.

- The resulting structure is referred to as a chart (Koṣṭaka).

Example:

Correlating Daṇḍakas and Dvāras

In the topic of Daṇḍaka Prakaraṇa, there are:

- 24 Daṇḍakas (types of punishment)

- 20 Dvāras (entry points or factors)

By arranging them in a tabular format, as shown below, their relationships become easier to understand and memorize.

📊 Sample Chart

(Daṇḍaka & Dvāra Correlation)

Interpretation of the Chart:

- Nārakas, Asurakumāras, and Nāgakumāras all possess 3 bodies, with varying capacities of Avagāhana (penetration space) — like 500 dhanushya or 7 haath.

- The Saṅghāṭana (consolidation capability) column indicates absence for all these cases.

| Type | શરીર (Body) | અવગાહના (Penetration) | સંઘયણ (Consolidation) |

|---|---|---|---|

| નારક (Nāraka) | 3 | 500 ધનુષ્ય | ન હોય |

| અસૂરકુમાર (Asurakumāra) | 3 | 7 હાથ | ન હોય |

| નાગકુમાર આદિ (Nāgakumāra etc.) | 3 | 7 હાથ | ન હોય |

Purpose and Advantages:

- Helps grasp multi-variable relationships clearly.

- Reduces complexity in memorizing vast scriptures.

- Highly effective for teaching, presentations, and structured learning in Jain studies.

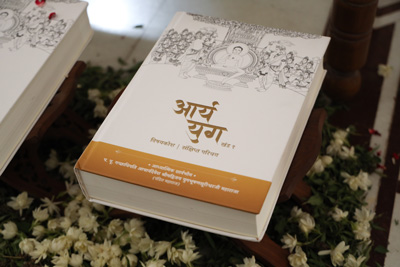

Recent Event

Aryayug Vishay Kosh unveiling ceremony.

Contact

5, Shrutdevta Bhavan, Jain Merchant Society, Paldi - 380007, Ahmedabad - India.

gitarthganga@gmail.com

+91 079 4003 4911

Follow Us